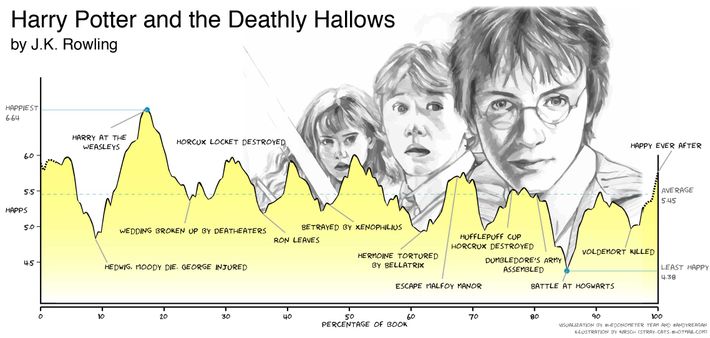

In his autobiography, Palm Sunday, Kurt Vonnegut

recalled the theme of a master’s thesis that got rejected by the University of Chicago. It was his “prettiest contribution” to culture, he wrote, and he carried the abstract of it in his head. “The fundamental idea is that stories have shapes which can be drawn on graph paper,” he writes, with good and ill fortune on the y-axis, and the duration of the story on the x-axis. One shape is the man-in-a-hole, he noted in a 1985

lecture, in which he expanded on his theory. “Somebody gets into trouble,” he said, “and gets out of it again.” This need not require man nor hole, but that parallel emotional arc.

In that lecture 31 years ago, Vonnegut mused about why computers hadn’t yet analyzed those shapes, since they

could already play chess. As of this month, analysts have made good on that speculation. For a

study published in

EPJ Data Science, a team lead by University of Vermont Ph.D. candidate Andrew J. Reagan took Vonnegut’s idea and, quantitatively, ran with it.

A

full 85 percent of the books analyzed fell under one of six shapes.

They are: ‘rags to riches,’ in which sentiment goes up; ‘riches to

rags,’ where it goes down; ‘man in a hole,’ in which there’s a fall,

then a rise; ‘Icarus’, where it’s a rise then a fall; ‘Cinderella,’ or

rise-fall-rise; and ‘Oedipus,’ or fall-rise-fall. The below charts show

what they look like:

To

find these arcs, Reagan and his colleagues pulled out a representative

subset of 1,327 stories from Project Gutenberg archive. With that corpus

in place, the researchers analyzed the happiness levels of the words

themselves, ratings that were found via

crowdsourcing the hedonic value of individual words (“love,” “laughter,” and “happiness” are at the top).

“To

generate the emotional arc for a book, we look at 10,000 word sections

of the book and measure the average happiness of the words in each of

these sections,” Reagan tells Science of Us. “As we move that window of

10,000 words through the book, we are able to see how the changes in

language throughout the book contribute to the happiness at each point,

and the resulting time series of happiness is the emotional arc.” It’s

not the plot of a story, with its various twists and turns, but the way

sentiment conveyed by the words themselves, and whether they rise or

fall, signaling happy or sad endings to chapters and sections and books

as a whole.

The authors used Harry Potter and the Deathly Hollows

as a case study. “While the plot of the book is nested and complicated,

the emotional arc associated with each sub-narrative is clearly

visible,” they write. When a story is good, the changes in emotionality

pull the reader along, even if there’s only so many variations of rhythm

in “happy parts” and “sad parts” that an author can throw at them. It’s

only formulaic if the formula shows.

©Martin Puddy

Cormorant fishermen in Li River

©Martin Puddy

Cormorant fishermen in Li River

nancy j wagner

nancy j wagner

History in Moments

History in Moments

SM Kennison

SM Kennison

Edward Wilkie

Edward Wilkie

Science GIFs

Science GIFs stan stewart

stan stewart

Mindfulness Training

Mindfulness Training

Great Minds Quotes

Great Minds Quotes